A Personal Note from Jo

First things first. Welcome to the 27 new faces who pulled up a chair at the Taste Jo Food table this week! It might not sound like a crowd to everyone, but to me, it’s a feast and I’m so glad you’re here!

Let’s continue the Turkish Black Sea Cuisine series and dive into a couple of cities along the Black Sea coast, starting with Sinop and then heading southwest to Kastamonu. I’ll share a bit about each location and highlight a few standout bites. This article is on the longer side, but I wanted to offer a detailed introduction to the flavors and dishes that left an impression on me. I hope it stirs your curiosity as well.

Before I get too far, if you missed last week’s newsletter, At the Crossroads of Sea and Soil: The Turkish Black Sea Cuisine, Part One, I encourage you to read that first. It sets the stage for this article and offers context for what makes this part of the country so distinct.

Sinop

From the airplane window, Sinop’s natural peninsula jutted dramatically into the Black Sea, a sight that hinted at the region’s unique geography. Perched on the northernmost edge of Türkiye, Sinop sits directly south of the Crimean Peninsula, its coastline cradled by water on three sides.

Historically, Sinop is one of Türkiye’s oldest cities, shaped by millennia of conquest and cultural exchange. Founded as a Greek colony in the 7th century BC, Sinop quickly became a key port on the Black Sea, later serving as a strategic outpost for the Romans, Byzantines, Seljuks and Ottomans. Its natural harbor and position along key maritime routes made it a hub of shipbuilding, commerce and diplomacy.

A small city far from the well-trodden tourist trail, Sinop is anything but trendy. While we were there, the locals looked genuinely puzzled when they saw a group of Americans wandering their streets.

“Why Sinop?” they asked.

“For the food,” I’d reply.

Their brows would unfurrow just a bit. “Oh… the mantı,” they'd say, nodding in sudden understanding.

Food of Sinop: Bites Worth Talking About

Sinop offers its distinct version of mantı, the beloved dumplings found across Türkiye. The dough is rolled thinner than the classic Anatolian style, giving each bite a more delicate texture. Rather than the traditional four-cornered pinch, Sinop-style mantı is folded into small triangles, more akin to East Asian dumplings. The final flourish is what truly distinguishes it: a generous spoonful of garlicky yogurt, red chili butter sauce and followed by a scattering of crushed walnuts, which adds a welcome textural contrast. We tasted the mantı at Sinop Örnek Mantı.

As mentioned in part one of the series (HERE), Sinop is known for its seafood, especially hamsi, or anchovies, which are best enjoyed during the winter months when they’re in season. Since we visited in May, we just missed peak hamsi time.

Still, we couldn’t leave Sinop without a proper seafood meal. One evening, a few of us sourced our dinner from a local fishmonger: fresh red mullet (barbun), which is local to the area and salmon. The fishmonger delivered our catch directly to the restaurant where we’d arranged to dine. That night, we savored a feast of grilled and lightly cornmeal-dusted fried fish, served alongside vibrant, herb-packed salads.

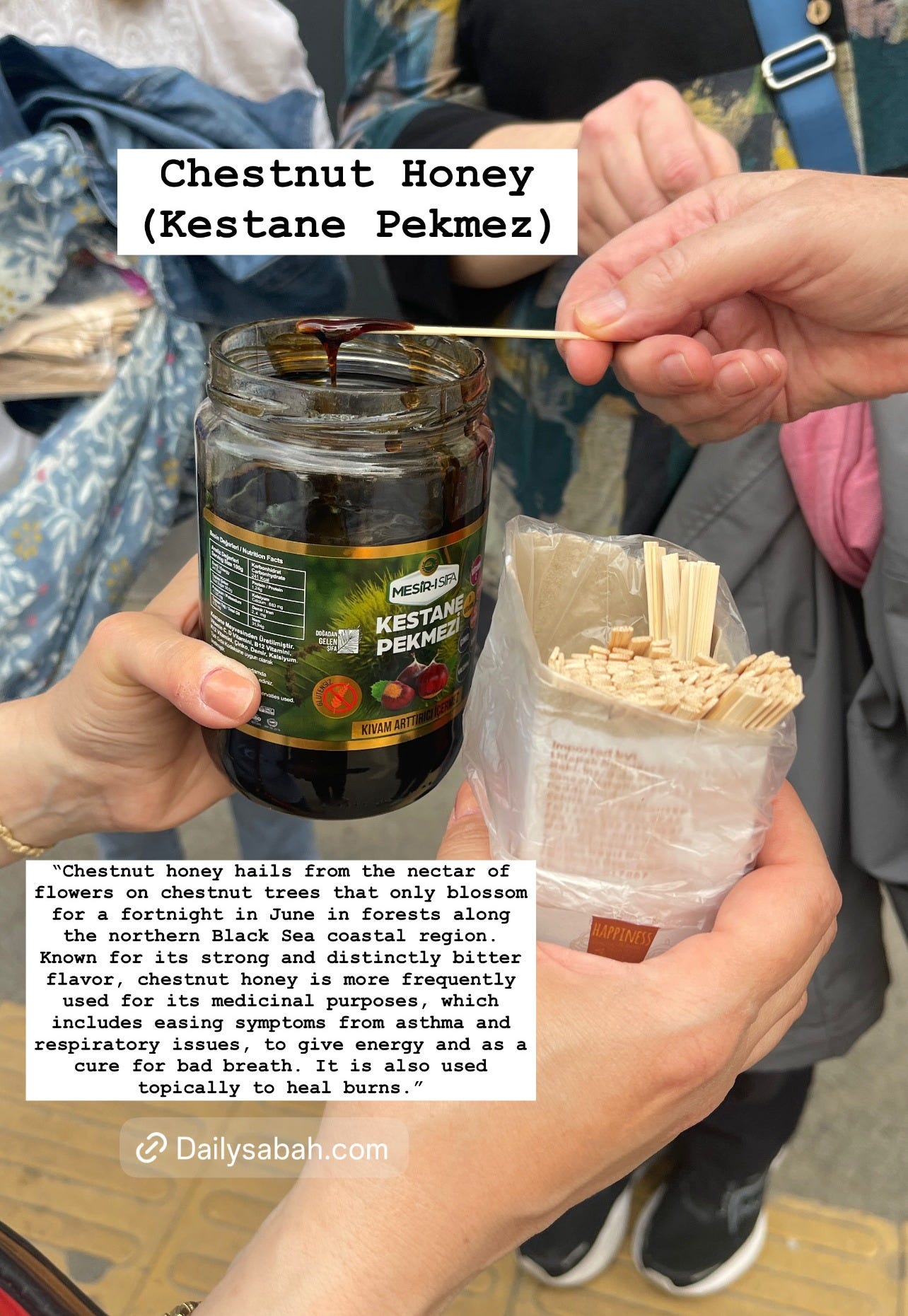

Chestnut honey, called kestane balı or kestane pekmez in Turkish, was completely new to me and I found its medicinal taste surprisingly enjoyable. As Daily Sabah explains, this unique honey comes from the nectar of chestnut tree blossoms, which bloom for just two weeks in June along the northern Black Sea coast. With its strong, distinct flavor, chestnut honey is traditionally used to help with respiratory issues like asthma, freshen breath and even treat burns when applied topically. I imagine it would be lovely stirred into a cup of tea or even worked into a cocktail to deepen the flavor of bitters.

Nokul, pictured above on the left, is a type of Black Sea börek, a spiraled pastry that can be either sweet or savory. The version we tried was filled with golden raisins, walnuts and sugar, then rolled into a tight coil of dough, brushed with egg yolk and finished with a sprinkle of sesame seeds. Some say it was a favored snack among the sailors of Sinop thanks to its portability and long shelf life. It’s the kind of pastry that pairs perfectly with a strong cup of çay.

Boyabat Ezmesi, pictured above on the right, was one of the best bites I tasted in Sinop. At its core, it’s a sweet nut-based dessert made by mixing warm syrup into toasted hazelnut butter, then shaping the mixture into portioned bites. I came across a Turkish chef making it on YouTube (linked below); the video is in Turkish, but subtitles can be turned on. The basic ingredients are hazelnuts (a big deal in Türkiye’s Black Sea region), sugar, water, flour, citric acid and whole walnuts to top.

Kastamonu

From Sinop, we headed southwest to Kastamonu, a city more than twice its size. Like Sinop, Kastamonu has deep historical roots in the Turkish Black Sea region, with archaeological evidence of human settlement dating back over 14,000 years. Over the centuries, it has played important roles in Ancient Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman civilizations. To read more about the city, check out this paper, “The Historical Kastamonu City in Türkiye” by Ahmet Hadrovic.

Today, visitors to Kastamonu can explore around 400 well-preserved Ottoman-era houses (konaklar), many of which were built by affluent families during the height of the empire. These historic homes, with their signature wooden façades and intricately carved interiors, offer a rare glimpse into the architectural elegance and domestic life of Ottoman high society in Anatolia.

For a deeper look at what it means to live in one of these houses today, consider reading “Kastamonu: The Ottoman Farmhouse” by Berrin Torolsan. In this article, Torolsan tells the story of a Turkish family that has inhabited the same Ottoman home in Kastamonu for generations.

Food of Kasatmonu: Bites Worth Talking About

While in Kastamonu, we had the chance to taste a wide variety of regional specialties and even joined a cooking demonstration led by three incredibly talented Boston-based chefs: Chef Ana Sortun (Executive Chef, restaurateur and cookbook author), Chef Chris Burton (Chef de Cuisine, Oleana) and Chef Amber Gouveia (Chef de Cuisine, Sofra). All three played a key role in organizing and guiding this trip.

During the demo, we learned how to make gözleme at home, as well as ekşili pilav, a tangy, yogurt-based “sour rice” native to Kastamonu. Their version featured einkorn bulgur, green onions and yogurt, all crowned with toasted hazelnuts (pictured below). It was bright, earthy and so satisfying. For another delicious take on this dish, check out this recipe.

Speaking of einkorn, this sturdy, resilient grain has deep roots in Türkiye and is steadily gaining popularity around the world, including in the U.S. Known as siyez in Turkish, einkorn is an ancient variety of wheat (read more HERE) that’s been cultivated for thousands of years, with the Kastamonu region being one of its main growing areas.

Cemre Torun, food editor, cook and consultant, wrote a standout piece for the anthology You and I Eat the Same, titled “The Good Stuff Doesn’t Sit Still.” In it, she highlights the work of Tangör Tan, a dedicated Anatolian foodways researcher collaborating with visionary Turkish chef Mehmet Gürs. Together, they’re at the forefront of the “New Anatolian Kitchen” movement, which aims to revive traditional regional ingredients and reimagine them through contemporary culinary practices. One key focus of their work is siyez bulgur. If this topic sparks your curiosity, I highly recommend picking up the book, it’s a rich collection of food stories from around the world.

During our trip, we sampled siyez in a few different forms, including some crisp, nutty crackers (cracker stick pictured below) that I loved. With its low glycemic index and impressive fat and protein content, it’s the kind of grain that deserves a spot in all our kitchens.

A few more regional bites and sips from Kastamonu that are well worth noting: Elma ekşisi (pictured in the glass above) is a drink made from local wild apples that are boiled down, strained and thickened into a tangy, slightly sweet concentrate. It's a deeply local drink that I think could be even more delicious if used as a base for a cocktail or cut with sparkling water, lots of possibilities to play with this drink.

Pastırma is a salt-cured beef at its finest. Once a preservation method used by nomadic Turkic tribes for storing cuts of meat, the technique has since evolved into something far more refined. To make pastırma, cuts of beef are rubbed with salt and air-dried for one to two months. Once dried, they’re coated in a fragrant spice paste made with garlic, fenugreek and paprika. When pastırma is ready for consumption, it is sliced very thin and then worked into all kinds of regional dishes, like etli ekmek (which becomes pastırmalı ekmek), stews or simply pan-fried with eggs for breakfast.

Banduma is a rustic, comforting dish made by layering tender pieces of boiled chicken over yufka that's been soaked in flavorful chicken or beef stock, then finishing it all with a generous drizzle of rich butter sauce and a sprinkle of crushed walnuts. I found a great video (below) that walks through the process if you're feeling inspired to try making it at home. This dish feels like a Turkish take on a good old Midwestern casserole. It is hearty, homey and meant to feed a crowd.

And finally, we end our time in Kastamonu on a sweet note. Çekme helva is Kastamonu’s most beloved dessert and for good reason. The recipe goes back hundreds of years and uses just a handful of ingredients: flour, sugar, butter, lemon and water. Similar to pişmaniye (or floss helva), it involves pulling and stretching a sugar syrup dough through a toasted butter and flour mixture until it reaches a texture of fine strands that are soft and silky. What makes Kastamonu’s version unique is that once the perfect consistency is achieved, it’s pressed into tidy cubes (pictured below). I’ve linked to a video, in Turkish, HERE that beautifully shows the process in action. Don’t miss the moment when they start pulling the sugar, it’s mesmerizing.

If you want to learn more about helva traditions across Türkiye, I wrote an article earlier this year called "Why Helva Belongs on Your Dessert Table."

I am still savoring my Kastamonu helva and will be really sad when we finish the last cube! I also remember the day they put that baduma on the table: everyone was SO FULL, and yet we FOUGHT over that dish. Thank you for these memories Jo!

Love these articles, so much interesting information. You’ve given me ideas for my next trip to Türkiye. Looking forward to part 3. Thank you